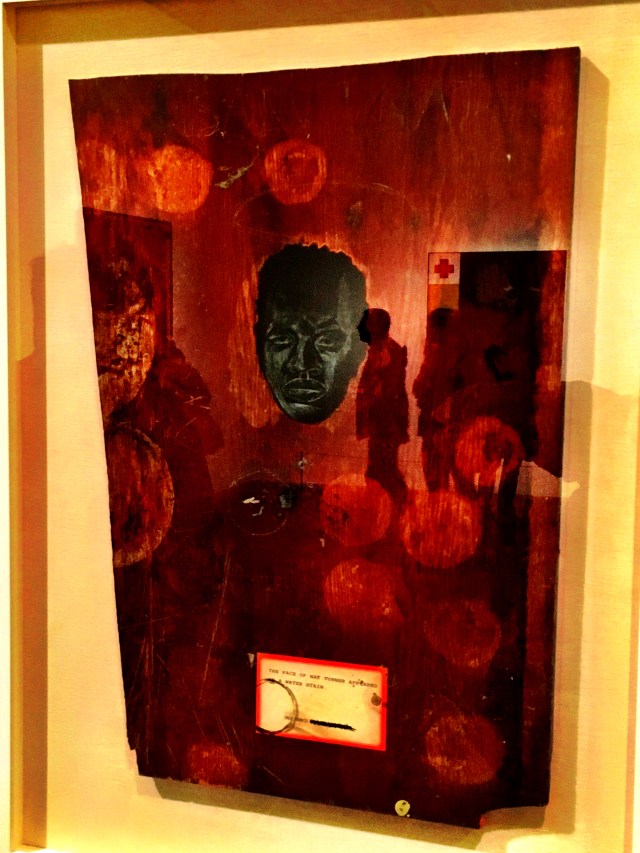

While in New York, my wonderful friends had planned a slew of great activities to attend during my stay. One of the most impressionable ones was at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Breuer, a show on Kerry James Marshall’s retrospective titled “Mastry”; and mastery is exactly what he displays. I fell in love with art as a child growing up in Hollywood and having elementary school field trips which exposed us to LACMA and the La Brea Tar Pits Museum. There lies an inexplicable fascination with the ability of someone, whom I have not met in person, to evoke feelings through a “muted” object of their own creation. To speak in a silent language, one that may be devoid of sound but not of breath. Marshall’s retrospection took me through a spectrum of emotion. From his beautiful series on Black love and romance, to the social critiques on the history of lynchings and police brutality, to depicting cultural spaces significant within U.S. African-American communities, the show is advertised as Marshall’s “largest museum retrospective to date,” yet leaves one wanting more. I was especially taken aback by the very first piece I saw from his show “The Face of Nat Turner Appeared In A Water Stain” (1990).

While the image obviously references an important historical figure within U.S. history of resistance, what struck me was his use of medium: a found object, a stained wood board where he painted the Nat Turner’s face. A small inscription in the foreground states reiterates the art piece’s title: “The face of Nat Turner appeared in a water stain.” What struck me about this piece was the influence I believe Mexican culture has had on Marshall’s work. Having lived in Los Angeles most of his life, this piece echoes with Mexican Catholic iconography, specifically with los retablos also used to commemorate the many, many saints and regional Virgin Marys.

While Marshall’s work is extremely minimal, incorporating his signature black tone paint, the reverence found in Mexican retablos is eloquently replicated in his piece. His work appears to also reference the constant appearance of Catholic figures such as Jesus and Virgin Mary, imprinting themselves on mundane items such as a tortilla, a tree stump, or even a grilled cheese sandwich. To have Nat Turner appear in a water stained piece of wood, would not be surprising provided the historical context Marshall gives his piece, a savior in human form, advocating for an oppressed group of people, choosing to clandestinely emerge not in a public forum like a church but instead on an intimate and disposable household item. The artist’s retrospective allows these and many other ideas to flow, Marshall’s 35-year career has documented an existence that continues to fight for their right to exist and persist. The show at the Met Breuer concludes at the end of this month and will make a quick transition to Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art in March. While it is not clear as to whether the curators will replicate the show with the same pieces I saw in New York, the exhibit without a doubt will resonate with Angelenos, sparking conversations on how Marshall’s career and his creations continue to speak in a language where words are simply not enough or even needed.

While Marshall’s work is extremely minimal, incorporating his signature black tone paint, the reverence found in Mexican retablos is eloquently replicated in his piece. His work appears to also reference the constant appearance of Catholic figures such as Jesus and Virgin Mary, imprinting themselves on mundane items such as a tortilla, a tree stump, or even a grilled cheese sandwich. To have Nat Turner appear in a water stained piece of wood, would not be surprising provided the historical context Marshall gives his piece, a savior in human form, advocating for an oppressed group of people, choosing to clandestinely emerge not in a public forum like a church but instead on an intimate and disposable household item. The artist’s retrospective allows these and many other ideas to flow, Marshall’s 35-year career has documented an existence that continues to fight for their right to exist and persist. The show at the Met Breuer concludes at the end of this month and will make a quick transition to Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art in March. While it is not clear as to whether the curators will replicate the show with the same pieces I saw in New York, the exhibit without a doubt will resonate with Angelenos, sparking conversations on how Marshall’s career and his creations continue to speak in a language where words are simply not enough or even needed.